November 1, 2025

Third Quarter 2025: Investment Perspective

MIND THE GAP

“ To think or dream that the present mania will subsist without a crisis the most severe ever experienced in this country would be to shut our eyes to all past experience.” — The Economist, 1845

“ Mechanically or scientifically, the railways, with all their multiplied conveniences and contrivances, are an honour to our age and country: commercially, they are great failures.” —The Economist, 1855

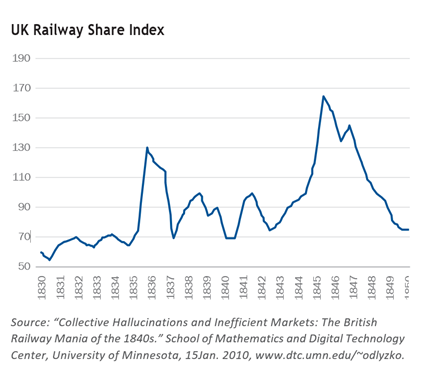

In the mid-1840s, England underwent a railway investment mania. The first railway lines had been built a decade earlier, and the returns to investors had been spectacular. Some of those original lines were by then paying 10-15% yields. In an investment landscape largely comprised of agricultural land (yielding 5%) and UK government loans (3-3.5%) those returns appeared magical. In 1844, Great Britain’s 2,000 track miles generated £5 million in revenue, against a national GDP of £500 million. Over the next three years, Parliament would approve 1,200 new lines entailing 8,500 track miles. The planned investment was £200-400 million. Based on the proposals submitted to Parliament, the expected revenues of the proposed lines would have had to reach £60 million, more than tenfold the 1844 revenues or roughly 12% of GDP by the early 1850s. To any reasonable person penciling out these numbers at the time, the economics would have appeared strained. But there was a fervor for the new technology and its ability to collapse time and distance.

The mania seized the entire country. The new ventures issued subscription certificates (‘scrip’)—essentially a type of pre-IPO share, since the companies had not received approval. Prices and volumes for scrips exploded. New stock exchanges were created in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Bristol and Birmingham to accommodate trading interest. Leeds had three competing exchanges and 3,000 stockbrokers. The railway operators’ shares were only partly paid, meaning shareholders were required to provide additional funds through capital calls to finance ongoing capital expenditures. By October 1845, the weight of capital calls began to draw money out of the speculation and the established companies sold off sharply. But that was only the beginning. In 1846, the total capital calls exceeded £40 million—roughly equivalent to the entire net profit of the British economy. The strain on the market for funds required the Bank of England to raise interest rates from 2.5% in 1845 to 10% by 1847. Banks and mercantile houses (commercial paper dealers) failed by the dozens. In early October, the Bank of England suspended all liquidity provision. It had less than half a million of bullion left. Finally, on October 23rd, the Prime Minister ordered the suspension of the Bank Act, so that the Bank could supply liquidity again. The financial melt-down was averted. But the shares of the railways would not find a bottom for several years falling 85% from peak to trough by 1850. The newly authorized lines had driven pricing lower, and the companies suspended dividends.

The devastation had reached into every corner of the country and deep into the middle class with an explosion in personal bankruptcies, asset forfeitures and imprisonments. A measure of how widespread the mania had been is that the Bronte sisters, living in a rural idyll (the filming location of All Creatures Great and Small), were swept up in the speculation. But for the financial success of Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights, they might have been financially ruined. Such that in late 1849, Charlotte Bronte could write:

“The business is certainly very bad—worse than I thought, and much worse than my father has any idea of. In fact, the little railway property I possessed, scarcely any portion of it can with security be calculated on…However the matter may terminate, I ought perhaps to be rather thankful than dissatisfied. When I look at my own case, and compare it with that of thousands besides—I scarcely see room or a murmur. Many—very many are—by the late strange Railway System deprived almost of their daily bread; such then as have only lost provision laid up for the future should take care how they complain.”

After a dramatic consolidation over the following decades and growth of the economy, British railroads would return to health. But even 50 years later with a network of 22,000 track miles the entire industry would contribute 6% of GDP. So the wildest expectations of the early promoters were never realized. The harsh reality was that revenues were 30-40% below expectations, construction costs were about 50% greater than expected and operating expenses were 30-40% higher than expected. Somehow the average UK railway investor was persuaded that the British rail network could expand by 4-5x and grow its aggregate revenues by 10x over 5-7 years. As with any mass delusion, we ask ‘what were they thinking?’

My pet theory is that every bubble is rooted in a fallacy of composition. What might apply to any individual member of the system cannot be true for the system as a whole. Every railway company’s business plan was only moderately overstated in terms of profitability and market share. Therefore, each investor’s discrete decision was in a narrow sense only marginally foolish. But when viewed in aggregate, the sum of all the business plans led to an absurdly exaggerated total profit pool. A lottery mentality takes over. Every lottery ticket buyer knowingly pays more than the expected value of a single ticket. They allow their dreams of wealth to disarm their reason. Another complication is that in any rapidly growing industry, its easy to confuse growth from capital employed for unit growth. British railway revenues had grown 10% per annum in the years preceding the Great Railway Mania—which in a stagnant economy could pass for secular growth. But capital employed had been growing at a similar rate. So investors may have been deluded as to the true underlying growth. Of course, there were also shenanigans perpetrated by the railway sponsors. Many companies were found to have paid dividends out of capital. But the fervor engendered by epochal miracles cannot be understated. The rails had reduced the trip from Glasgow to London from four days to 24 hours. The same rail journey today takes 4 ½ hours. So the same order-of-magnitude improvement that occurred in the first 15 years of rail travel would subsequently require 150 years. The point is that an initial step change can give people a false sense of the long-term feasible rate of change. The last point is simply information asymmetry. Emily Bronte conducted the operations of the Bronte sisters in the stock market. She apparently read the offering memos assiduously, but it’s doubtful she could have formed a variant opinion from what she read from the promoters.

Today we find ourselves in the throes of another capital boom tied to a novel invention. Many observers compare the AI investment boom to prior investment surges—particularly the TMT boom of the late 1990s. The typical line of reasoning is to compare the two along quantitative metrics. They point to the tremendous demand driven revenue trajectory at select companies today that they argue was absent in that earlier time. Another difference is the financial wherewithal of the leading companies now as opposed to the considerably shakier corporate structures of the dot-com era. The argument is that the different circumstances argue for different outcomes. I see differences too. And they’re not benign. By 1845, the business model of moving freight and passengers by rail was proven. The new railway companies employed traffic takers to assess the existing canal and stagecoach traffic on routes to determine the line’s market potential. So these estimates were vulnerable to error, but there were at least somewhat defined boundaries. My subjective judgment is that today’s AI business are subject to greater uncertainties by orders of magnitude. Not the least of which is competition. A simple question—how many foundational large language models will the market allow and at what level of unit economics? Even the Victorians understood that no single route could tolerate more than two lines before the tariffs would become uneconomic. We now have at least six major contenders each investing tens of billions. But what is rational for each executive team and sponsor—pursuing monopolistic rents for decades—is less sensible in the aggregate. Asset allocators—writ large—own them all. While there’s a future Jeff Bezos lurking out there in the LLM derby—investors effectively must write off the dry holes against the select winners. Another difference today is the obsolescence of the capital. Both chips and foundational models are advancing a generation in two years. So the development costs entail a pay back period of 5-7 years—roughly three generations. Whatever can be said about the Victorian rail magnates, they built infrastructure for decades.

None of this should be construed as a Luddite opposition. If you throw a trillion dollars and sufficient numbers of MIT trained engineers at a problem, it’s reasonable to expect some pretty astounding technological breakthroughs. You can be at once bullish on AI and bearish on the current AI investment boom. For those old enough to remember the Dover-Calais ferry, stepping on the Eurostar in St. Pancras Station is something of a marvel. But the Eurotunnel went bankrupt twice and turned out to have been a negative net present value for society. And in some circles that exact cynical resolve is taking hold. The CEO of leading venture capital firm General Catalyst recently said “Bubbles are good. Bubbles align capital and talent in a new trend, and that creates some carnage but it also creates enduring, new businesses that change the world.” I might have asked a follow-up. “Can you please expand on the ‘carnage’ part of your comment?”

My conclusion is that there is more alike than different between today’s investment fervor and other periods of misplaced euphoria. I see that same unbridled optimism in miraculous change, the same telescoping of a distant future into valuations, the same generalization of individual successes to whole markets, the same chasing behaviors among investors. That argues for some moderation in investment risk. We believe we have ample exposure to the potential transformative applications through our venture program. We also have ample positions in infrastructure build-out and platforms enabling the expansion of compute demand. But we have moderated those positions somewhat in this quarter. We added to low volatility stocks and reduced our higher beta technology exposure in our U.S. portfolios We maintain our overweight to European stocks and duration in fixed income as potential hedges against a reversal in overextended sentiment. At this point, it feels prudent to patiently wait for a ticket on the Eurostar rather than plunge all our fortunes into building the channel tunnel.

—T. Brad Conger, CFA

Chief Investment Officer

On a quarterly basis, Hirtle Callaghan publishes our perspective on the current market. If you would like to be added to our distribution list and receive the full version of our latest Investment Perspective piece, please contact us.

To download a PDF of the excerpt, click here: Investment Perspective 3Q 2025 Excerpt.